Ethnic Identity of Jewish People: A Controversial Concept

Jews want the world to see them as a people with a history of self-governance in ancient times who documented their historical records in the Bible. After that, they went underground for many centuries, and then they emerged at last only to be slaughtered by the Nazis; finally, they established Israel, a controversial state.

The concept of Jewish Identity has been a subject of debate. While some argue that shared religious beliefs and historical experiences bind Jews together as a nation, others argue that this is a misleading oversimplification. As Shlomo Sand points out, the term ethnic is used in cases such as “the people of France,” “the people of America,” and “the people of Vietnam.” Therefore, referring to “Jewish people” is as strange as referring to “Buddhist people” or “Evangelical people” [1]. The idea of a unified Jewish people, distinct from other nations, has been a cornerstone of Jewish identity, but it has also been a source of discord and contributed to ethnocentric beliefs and behaviors. Jewish people consider themselves higher than other nations and believe they are spiritually different from others. This paper investigates the history of this ethnography. It is also noted that this extreme form of ethnic historiography has united Jews from around the world with the intention of taking over the land of Palestine and establishing the state of Israel. This racist ethnocentrism has led to the displacement of the indigenous people of the region through the distortion of historical narratives. This issue is important since this ethnocentrism has led to racism and superiority.

Origins and Beginnings

The Hebrew Bible traces the origin of Israelites back to Abraham, a figure who migrated from Ur of the Chaldees to the land of Canaan. Abraham’s descendants, Isaac and Jacob (Israel), are central figures in biblical narrative. Jacob’s twelve sons became the patriarchs of the twelve tribes of Israel.

The Israelites in the Hebrew Bible

The term Hebrew first appears in Genesis in reference to Prophet Abraham [2]. Joseph, Jacob’s son, uses the term to describe both a geographical location and an ethnic identity [3].

Prophet Abraham was the first Muslim Hebrew; as the Quran states: “He (Abraham) was not Yahuudiyyan, ‘a Jew’, nor Nasraaniyyan, ‘a Christian,’ but rather a Haniifan, i.e., ‘a monotheistic Hebrew believer submitting (Islam) to the one imageless God who created all space and time’ [4]. The name Israel is first bestowed upon Jacob; it is derived from the Hebrew verb “to struggle” and reflects Jacob’s spiritual struggle [5].

Jews in the Quran

In the Quran, Jews are not introduced as a race but as a religious group, while the children of Israel are mentioned as a people. The Quran’s view of Jews is relatively negative, but the children of Israel are a people that the Quran looks at from different angles. The word Jew in the Holy Quran refers to a new concept that was formed by Jewish people in the first centuries AD. A clear example is the Jewish centers at the time of the Prophet of Islam (PBUH), which were mainly located in Mesopotamia and Arabia and were engaged in monetary exchanges based on interest (usury), an act that the Quran strongly condemns.

Among the People of the Book, there were good and bad people from all classes. Those who were guided and righteous embraced the book and Sharia (religious rulings) of Prophet Moses with heartfelt acceptance and remained firm on his Sharia even after the death of Moses. They had faith in Prophet Moses and believed the book of Torah was revealed to him [6].

But the evil ones killed many prophets. They disobeyed Allah and His Messenger and engaged in wrongdoing. In the Holy Quran, they are described as rebellious transgressors, with many displaying disobedience and engaging in evil deeds [7].

When the Quran refers to Jews, it means this group of Jews. They are described as extremely ungrateful and greedy for the world [8]. They have nothing to do with Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, and Jacob’s children because they have hidden the Book of God and preferred misguidance over guidance [9]. Because of breaking the covenant, disbelief in the revelations of God, and the killing prophets, God has put a seal on their hearts and they will not believe, except a few of them [10]. Moreover, because of engaging in usury and devouring people’s property, a painful punishment awaits them [11]. They are deniers, the enemies of God’s message, corrupters on earth, and cursed by God [12]. In fact, God calls them the party of Satan [13].

The Jewish Nation

The Jewish nation is attributed to Judah, the fourth son of Jacob. At the end of Jacob’s life, Judah was the head of the largest and most populous tribe of the Israelites, and from then on, his tribe was considered the most important political power of the Israelites. In Jewish mythology, which has played an important role in the development of Jewish culture and ethnic psychology, Judah is the cleverest and most prominent of Joseph’s rival brothers, and his character is considered an acceptable model for Jewish people [14].

However, Judah is the symbol of deceit among the sons of Jacob. On the one hand, he plays the main role in the story of the brothers’ conspiracy against Joseph’s life; on the other hand, he deceives Jacob, blaming his brothers for Joseph’s disappearance while posing as Joseph’s savior and friend. With this trick, he finally becomes Joseph’s successor and the ruler of Israelites.

According to the Quran, this spirit of jealousy and superiority in Judah and his brothers led them to throw Joseph into a pit: “When they said, ‘Certainly Joseph and his brother are dearer to our father than we, though we are a (stronger) company; most surely our father is in manifest error [15].’” This attitude persisted within the Jewish community, resulting in the Torah’s strongest condemnations being directed at them.

Judah Halevi, in his philosophical work Kuzari, posits that Jewish people possess a unique spiritual essence that sets them apart from other nations. He argues that each Jew inherits a prophetic potential, a divine gift that allows them to understand God’s will. Even a convert to Judaism, despite their acceptance into the faith, cannot fully attain this innate spiritual capacity, as they lack the inherent spiritual DNA of a Jew born into the tradition [16].

Dr Ronit Lentin in “Palestinians Lives Matter” says, “Jewish people, on the other hand, have been constructed by Zionist thinkers as racially supreme, and homogenized by theorists of ethnicity in the Israeli context” [17].

This ideology underpinned the establishment of Israel as a nation-state exclusive to Jewish people. According to Israel’s Law of Return, Jewish identity is determined not by religious belief but by a person’s Jewish ancestry. While conversion to Judaism is possible, the process is rigorous and the number of converts remains relatively small [18].

To address the challenge of integrating non-Jewish people into the Zionist project and settling them in the promised land, some Kabbalistic ideas were employed to facilitate conversion. Some Kabbalists believed that gentile converts already possessed a Jewish soul that had become lost among non-Jews, perhaps due to a Jewish ancestor’s forced baptism. They saw a person’s conversion to Judaism as returning to their true origin, believing a latent Jewish essence drew them back to Judaism [19]. With this justification, they provide the grounds for the immigration of the people who join the Jewish faith.

Migration to Egypt and Enslavement

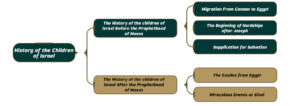

The history of the children of Israel changes dramatically with the emergence of Prophet Moses. Therefore, this history is divided into the era before the prophethood of Moses and after it. Refer to Fig. 1 for illustration.

Fig.1. The history of the children of Israel before and after the prophethood of Moses

According to the Book of Genesis, Joseph, one of the twelve sons of Jacob, was sold into slavery and eventually rose to a position of great power in Egypt. When a severe famine struck the region, Joseph’s family migrated to Egypt to seek refuge. Initially welcomed and provided for, the Israelites thrived under Egyptian rule.

However, this period of prosperity was not to last. The biblical text explains this shift:

A new king, who did not know Joseph, came to power in Egypt. He said to his people, “Look, the Israelites have become too numerous and powerful for us. Come, let’s deal shrewdly with them so that they do not increase in number. If war breaks out, they will join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land.” [20]

This shift in Egyptian policy marked the beginning of the Israelites’ enslavement. The exact historical context for this change is debated by scholars, but some theories suggest that the rise of a new pharaoh after the death of Akhenaten, who had a more tolerant religious policy, could have led to increased persecution of the Hebrews.

There is evidence suggesting that the period of Egyptian oppression that led to the Israelite revolt and Exodus occurred in the late second millennium BC, likely during the reign of the famous Ramesses II (1304-1237 BC). The opening of the Book of Exodus states that Egyptians set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens. And they built for Pharaoh store-cities, Pithom, and Rameses [21].

Moses and the Exodus

It was during this period of oppression that Moses emerged as a pivotal figure. Raised in the Egyptian royal court, Moses became aware of the suffering of his people. His divine calling led him to confront Pharaoh and demand the release of Israelites [22].

The Quran and Torah both recount the story of Moses and Israelites. According to both texts, Moses was chosen by God and led Israelites out of Egyptian slavery [23]. After a period of wandering in the Sinai desert, Israelites reached the outskirts of Canaan, the promised land. However, they refused to enter and fight the inhabitants, fearing their strength. As a result, they were forced to wander for forty more years as punishment [24].

In his book, The Invention of the Land of Israel, Shlomo Sand examines the concept of the promised land: “Few people have noticed, or are willing to acknowledge, that the Land of Israel of biblical texts did not include Jerusalem, Hebron, Bethlehem, or their surrounding areas, but rather only Samaria and a number of adjacent areas [25].”

Both religious texts agree on the reason and duration of this wandering period. The Israelites spent most of these forty years in the Kadesh Barnea region of the Sinai desert [26].

The Israelites: A History of Disobedience

After Moses saves Israelites from Egypt, they continue their ungratefulness: “And they said to Moses, ‘Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you brought us to the desert to die? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt?’” [27].

And in another situation, they make an excuse:

The Israelites said to them, “If only we had died by the Lord’s hand in Egypt! There we sat around pots of meat and ate all the food we wanted, but you have brought us out into this desert to starve this entire assembly to death.” [28]

One of the most significant instances of their disobedience occurred shortly after their miraculous Exodus from Egypt. Led by Moses, they had wandered through the wilderness for forty years. While Moses was on Mount Sinai receiving the Ten Commandments, the Israelites, growing impatient and influenced by their former Egyptian ways, constructed a golden calf and began to worship it. This act of idolatry was a grave sin in the eyes of God, who saw it as a rejection of His covenant with them:

And Moses made haste, and came down from the mount, and the two tables of the testimony were in his hand. And when he came down from the mount, and saw the calf, and the dancing, Moses’ anger waxed hot, and he cast the tables out of his hands, and brake them beneath the mount. And he took the calf which they had made, and burnt it with fire, and ground it to powder, and strewed it upon the water, and made the children of Israel drink it. [29]

The Establishment of the Israelite State

Upon their entry into the land of Canaan under the leadership of Joshua, the Israelites began the process of settling and establishing themselves in their promised land. This period, following the conquest, is often referred to as the era of the Judges.

Regarding the use of the name Canaan in distorted scriptures, Shlomo Sand explains:

because a United Kingdom encompassing both ancient Judea and Israel never existed, a unifying Hebrew name for such a territory never emerged. As a result, all biblical texts employed the same pharaonic name for the region: the land of Canaan. [30]

The Period of the Judges

After Joshua, Israel did not have a single, centralized monarchy. Instead, the nation was led by a series of charismatic individuals known as Judges. These leaders were raised up by God to deliver the Israelites from various oppressions and to unite the tribes. The book of Judges in the Hebrew Bible provides detailed accounts of these judges, their exploits, and the cycles of sin and repentance that characterized this period [31].

Brave leaders called Judges, some twelve in number, set their faces against these soul-sapping idolatries; appearing on the scene as liberators from the enemy’s pressure, they succeeded in recalling people to the pure worship of YHWH [32].

The Monarchy and Subsequent Divisions

Jews do not recognize David and Solomon as prophets. Instead, they view them as their first kings and symbols of their power and greatness. Modern Jewish myths differ significantly from the historical narratives about David and Solomon that were common among Arabs and others. The Old Testament is the only source for the claim that the royal house of Judah descended from David. This text has been subject to numerous revisions and distortions over the centuries, particularly during the Babylonian Exile.

The United Monarchy

Around 1000 BCE, Saul was appointed as the first king of Jewish people. Prophet David succeeded him, captured Jerusalem, and established it as the capital. Prophet David’s son, Prophet Solomon, built the magnificent Temple in Jerusalem, which became the religious center for people [33].

With David (c. 1012–972), his successor, began Israel’s golden era. He quickly rallied the tribes about him, and by a series of brilliant military victories, he extended his kingdom from Phoenicia in the west to the Arabian Desert in the east, and from the river Orontes in the north to the head of the Gulf of Aqaba in the south. Most far-reaching in its consequences was his capture of the last of the Canaanite strongholds in the land, the impregnable Jerusalem. The worship of YHWH was now well-established throughout the land. David’s policy of political and religious centralization was carried on and developed by his son and successor, Solomon (c. 971-931). In order to centralize the cult, Solomon built a magnificent Temple in Jerusalem as the sole legitimate place of worship, superseding all others in the land, a status previously held by Shiloh before its destruction. [34].” As you can see in Fig. 1, this glorious era of united monarchy ended with the rebels of the Jews and the Israelites against each other.

Division of the Kingdom

After Solomon passed away, the Kingdom fractured into two separate realms: the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah. This division severely weakened Jewish power and influence [35].

Israel Rebels Against Rehoboam

1 Kings describes how Rehoboam, king of Judah, caused the division of Israel:

Rehoboam (Solomon’s son and King of Judah) went to Shechem, for all Israel had gone there to make him king. When Jeroboam (son of Nebat and the leader of the House of Joseph) heard this, he returned from Egypt. So, they sent for Jeroboam, and he and the whole assembly of Israel went to Rehoboam and said to him, “Your father put a heavy yoke on us, but now lighten the harsh labor and the heavy yoke he put on us, and we will serve you…” Rehoboam said, “My father laid on you a heavy yoke; I will make it even heavier. My father scourged you with whips; I will scourge you with scorpions.” [36]

Jewish Rebellion Against the Israelites

The gathering of the tribal leaders in Shechem indicated that they did not recognize the centrality of Jerusalem, which was now seen as a center for idolatry. Therefore, the land of Israel was divided into two kingdoms: the Kingdom of Ephraim and the Kingdom of Judah. After the independence of the Kingdom of Ephraim, there were long years of political strife and bloody warfare between the two kingdoms. The cause of these conflicts was the antagonistic policy of the Kingdom of Judah and the House of David, who considered themselves chosen by the God of Israel and as shepherds of Israel; they claimed for themselves the right to rule over all the tribes of Israel [37].

This conflict continued until God forbade Jewish people from fighting with Israelites:

But this word of God came to Shemaiah the man of God, Say to Rehoboam son of Solomon king of Judah, to all Judah and Benjamin, and to the rest of the people, “This is what the Lord says: Do not go up to fight against your brothers, the Israelites.” [38]

The first conspiracy of the Jewish aristocracy against the Kingdom of Ephraim began immediately after the ten tribes of Israel declared their independence: “King Rehoboam sent out Adoniram, who was in charge of forced labor, but all Israel stoned him to death. King Rehoboam, however, managed to get into his chariot and escape to Jerusalem” [39].

Modern Jewish historiography also adopts a selective and biased approach to these events. For example, the Jewish Encyclopedia attributes the opposition of Ahijah the Shilonite to Solomon’s tolerant policy towards foreign religions. In other words, Solomon is portrayed as a liberal king and Ahijah the Shilonite as a fundamentalist prophet! However, Ahijah was not concerned with tolerance but with the replacement of Mosaic traditions with Phoenician Baal worship during Solomon’s reign. The same source presents Jeroboam as the reviver of the worship of the golden calf in Israel, along with a 12th-century Spanish Jewish image depicting Jeroboam and his people worshipping the golden calf. This approach clearly indicates that modern Judaism consciously sees itself as the sole heir to the traditions of the tribe of Judah and not of all of Israel [40].

The Babylonian Exile

In 586 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon, conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple. Many Jews were exiled to Babylon. The Bible, however, directly attributes the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple, and even the Babylonian Exile, to the kings of Judah, who “did what was evil in the sight of the Lord” [41].

This period of captivity, known as the Babylonian Exile, had a profound impact on Jewish culture and religion.

Return from Exile and Reconstruction

With the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, the King of Persia, Jews were permitted to return to their homeland. The Second Temple was rebuilt in Jerusalem, marking the beginning of a new era in Jewish history [42].

The Diaspora and Jewish Dispersion

Following numerous rebellions against Roman rule and the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Jews claim that they were scattered throughout the Roman Empire and beyond. This marked the beginning of the Diaspora.

However, it is astonishing how little research has been done on this supposed historic event in Jewish history, which is considered the basis for the Diaspora or the dispersion of Jewish people. The reason is quite simple: The Romans never exiled any of the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean. Except for those enslaved, the inhabitants of Judea continued to live on their land even after the destruction of the Second Temple. A portion of them converted to Christianity in the 4th century CE, while the vast majority converted to Islam upon the Arab conquest in the 7th century CE. Most Zionist scholars were aware of this. Yitzhak Ben Zvi, who later became the president of Israel, and David Ben-Gurion, the founder of the State of Israel, mentioned this as late as 1929, during the great Palestinian uprising. Both repeatedly noted that the peasants of Palestine were the descendants of the inhabitants of ancient Judea [43].

In his book Ten Myths About Israel, Ilan Pappe writes:

When the Ottomans arrived, they found a society that was mostly Sunni Muslim and rural, but with small urban elites who spoke Arabic. Less than 5 percent of the population was Jewish and probably 10 to 15 percent were Christian. As Yonatan Mendel comments: “The exact percentage of Jews prior to the rise of Zionism is unknown. However, it probably ranged from 2 to 5 percent.” According to Ottoman records, a total population of 462,465 resided in 1878 in what is today Israel (Occupied Palestine). Of this number, 403,795 (87 percent) were Muslim, 43,659 (10 percent) were Christians and 15,011 (3 percent) were Jewish. [44]

Jews in the Roman Empire

Jews claim they sometimes enjoyed relative freedom and were sometimes persecuted during the Roman Empire. With the spread of Christianity, the situation of Jews became more complex. However, it seems that their culture and life were mixed with the Romans and even influenced many of their religious and philosophical customs.

Some scholars, like Ellen Miller, argue that the concept of Jewish people only emerged around the 1st century CE [45]. Judah ha-Nasi, a prominent Jewish leader in the early centuries of Christianity, played a crucial role in shaping modern Judaism. He is often referred to as Rabbi and is considered the founder of the Mishnah, a collection of Jewish oral traditions. Judah ha-Nasi established a religious center and school, solidifying his authority. To legitimize his leadership, Judah ha-Nasi linked himself and the Jewish elite to the House of David. This created a unified identity for the Jewish community. The Mishnah provided a framework for Jewish life and helped to preserve Jewish identity [46]. In many examples, especially in the life of Judah ha-Nasi, rabbinic traditions have had a deep connection with wealth accumulation and political power struggles from the beginning.

Jews in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, Jews lived in Europe and the Middle East. During certain periods, especially in Muslim Spain, they enjoyed cultural and economic prosperity. Later, in 612, King Sisebut reversed these rights and began forcing Jews to convert to Christianity. This policy was briefly interrupted in 640 when King Chindasuinth came to power and was more tolerant of Jews. However, in 653, King Recceswinth, reintroduced strict laws, making life difficult for Jewish people in Spain. However, Jews played a role in helping Muslim invaders conquer Spain, which ultimately ended the Visigothic rule.

During the Carolingian Dynasty, Jews in Francia enjoyed a relatively peaceful existence. They were valued for their role in trade with the East and were allowed to practice their religion freely. However, they were forbidden from converting Christians. During this time, many Persian Jews immigrated to Francia, bringing their own customs and traditions. Over time, they assimilated into the broader Jewish community in Europe, which would later become known as Ashkenazi Jews.

The peaceful period ended with the First Crusade. Despite facing challenges, German Jews continued to develop their own unique culture, language (Yiddish), and traditions. They also established a significant role as Court Jews within the Holy Roman Empire [47].

Jews and Christians in Medieval Europe

The relationship between Jews and Christians in medieval Europe was sometimes tense. Christians blamed Jews for the death of Jesus and pressured them to convert to Christianity. Some of these claims are now questionable. Some historians argue that Jews were more integrated into Christian society than previously believed. Historian Jonathan Elukin argues, in his book Living Together, Living Apart, that during the Crusades, some Jews found protection and refuge among Christians. Some Jews even worked in Christian villages, and there were instances of conversion to Judaism and interfaith marriages [48].

Palestine During the Ottoman Period

The traditional historical narrative often presents a different picture of Palestine during the Ottoman era. Rather than being an isolated and backward society, it was a vibrant and dynamic part of the broader Eastern Mediterranean region. It was open to cultural exchange and modernization, with cities like Haifa, Shefamr, Tiberias, and Acre experiencing significant development under local leaders like Daher al-Umar.

Coastal cities flourished through trade with Europe, while the inland areas engaged in commerce with neighboring regions. Palestine was a fertile land with a thriving agricultural industry, supporting a population of around half a million people. This contradicts the common notion of a desolate and underdeveloped region before the arrival of Zionism [49].

The Jewish Narrative: A Cover for the Establishment of Israel

While Jewish history in the Middle Ages experienced many ups and downs, historical records consistently show that Jews lived, traded, and practiced their faith alongside the followers of other religions. Some Jewish historians have cited instances of violence and torture against Jews, though the veracity of these claims is debated by other historians. Nevertheless, such historical narratives, which do not seem very real, were not unprecedented in the history of this nation, nor did they stop after that. These claimed acts of oppression justified Zionism’s quiet conquests in the name of Jewish people and ultimately led to the formation of a Zionist government in Palestine.

Conclusion

Jews have long positioned themselves as a symbol of the world’s homeless and marginalized victims of persecution by other nations. They argue that the solution to this plight lies in the modern-day state of Israel (Occupied Palestine), established to embody a humanitarian ideal. However, the harsh realities of survival in a hostile world have necessitated a more pragmatic approach towards them!

Recent historical research challenges this narrative. It reveals that after the death of Solomon, Jewish tribes fractured into warring factions, sowing the seeds of their own dispersion. Centuries later, Zionism sought to unite Jews worldwide by emphasizing a shared Jewish identity. Then it convinced them to return to the promised land. However, this land was never uninhabited, and Palestinian people were its original inhabitants.

As Ilan Pappe states in his book Ten Myths About Israel:

Nothing like that could happen if we continue to fall into the trap of treating mythologies as truths. Palestine was not empty and the Jewish people had homelands; Palestine was colonized, not “redeemed”; and its people were dispossessed in 1948, rather than leaving voluntarily. Colonized people, even under the UN Charter, have the right to struggle for their liberation, even with an army. [50]

This myth-making, used to obscure the truth and pursue illegitimate aims, has presented a profound historical challenge for Jews—a bitter truth long understood by many within the community.

References

[1]. Sand, Shlomo, The Invention of the Land of Israel from Holy Land to Homeland, Translated by Geremy Forman, London, 2014, 15.

[2]. Genesis 14:13

[3]. Genesis 40:15, 43:32

[4]. Quran, 3:67

[5]. Maller, Rabbi Allen S., “Who are Children of Israel (Bani Israel)?” Islamcity, 2022:

https://www.islamicity.org/79910/who-are-children-of-israel-bani-israel/

[6]. Quran, 5:66

[7]. Quran, 5: 66, 57: 16

[8]. Quran, 2:96

[9]. Quran, 2:140

[10]. Quran, 4:155

[11]. Quran, 4:161

[12]. Quran, 5:64

[13]. Quran, 58:19

[14]. Judaica, Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem, vol.10, 332.

[15]. Quran, 12:8

[16]. Unterman, Alan, Jews, their Religious Belifs and Practices, Routledge, London and NewYork,1990, 277.

[17]. Lentin, Ronit, “Palestinians lives matter Racialising Israel: Settler-colonialism”, Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies, 19.2 (2020): 133–149

[18]. Law of Return – Adalah:

www.adalah.org/en/law/view/537

[19]. Unterman, Alan, Jews, their Religious Belifs and Practices, Routledge, London and NewYork, 1990, 228.

[20]. Exodus 1:8-10

[21]. Johnson, Paul, A History of The Jews, Harper Perennial, New York City and London, 1988, 25.

[22]. Epstein, Isidore, Judaism: A Historical Presentation, England, 1959, 15.

[23]. Quran, 20:9-13

[24]. Numbers 13:27-33

[25]. Sand, Shlomo, The Invention of the Land of Israel From Holy Land to Homeland, Translated by Geremy Forman, London, 2014, 25.

[26]. Numbers: 14:40

[27]. Exodus 14:11

[28]. Exodus 16:3

[29]. Exodus 32: 19-21

[30]. Sand, Shlomo, The Invention of the Land of Israel From Holy Land to Homeland, Translated by Geremy Forman, London, 2014, 25.

[31]. Zeidabadi, Ahmad, Religion and Government in Israel (In Persian), Tehran, Rozengar, 2002, 25-26.

[32]. Epstein, Isidore, Judaism a historical presentation, London, 1959, 32.

[33]. 1 Samuel 8:11

[34]. Epstein, Isidore, Judaism a historical presentation, London, 1959, 34.

[35]. Myers, David, Jewish history: a very short introduction, Oxford University Press, New York, 2017.

[36]. 1 kings 12:1-14

[37]. Jewish Studies Centre, The Jewish aristocracy and the state of Ephraim (In Persian):

[38]. 1 Kings 12: 23-24

[39]. 1 kings 12: 18

[40]. Shahbazi, Abdullah, Jewish and Persian rulers, British and Iranian colonization (In Persian), Tehran: Institute of Political Studies and Research, second edition, 2010, vol. 1, 323.

[41]. 2Kings 23:32, 23:37, 24:9, 24:19

[42]. Isaiah 45:4–5, Bible Gateway passage: 2 Chronicles 36, New Living Translation. Bible Gateway, Retrieved 2023.

[43]. Jewish Studies Centre, The myth of diaspora or displacement (In Persian):

[44]. Pappe, Ilan, Ten Myths About Israel, Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books, 2017, 15.

[45] . Miller, Rabbi Alan W., Hebrews, Americana, vol. 14, 40.

[46]. Shahbazi, Abdullah, Jewish and Persian rulers, British and Iranian colonization (In Persian), Tehran: Institute of Political Studies and Research, second edition, 2010, vol. 1, 418.

[47]. Bachrach, Bernard, Early Medieval Jewish Policy in Western Europe, Minnesota Press, 1977, 26.

[48]. Elukin, Jonathan, Living Together, Living Apart: Rethinking Jewish-Christian Relations in the Middle Ages, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007, 82.

[49]. Pappe, Ilan, Ten Myths About Israel, Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books, 2017, 15.

[50]. Ibid, 281.

2 Responses

Good shout.

Thanks for the positive comment! We’re always striving to make our documentation clear and helpful.